Here’s a thought, did people in the Middle Ages have a concept of ‘being on time’? You started work as soon as it was light enough, and there were no 10:00 appointments to be on time for – or so I thought until I started researching the medieval clocks of the Monastery.

Before this my understanding was the only thing you had to be on time for was Mass, and if you lived in Worcester the cathedral bells rang out the canonical hours over the city and you could always hear them, so would always be on time. But….how did the monks know when to ring the bells for Mass?

They used a ‘clock,’ but not a clock as we know it today.

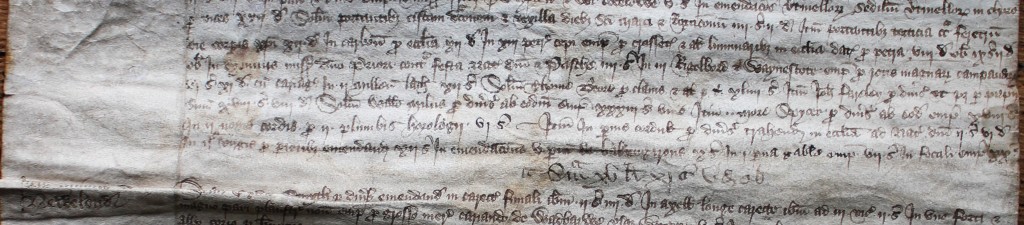

A Worcester Register1 recording the business of the Priory during the period after the death of Bishop Giffard in February 1301 to the Enthronement of Bishop Ginsborough in June 1303 shows that the community had an accurate perception of the ‘hour’, with several references to somebody attending the Cathedral at a specific hour. Also they are using secular hours not liturgical hours, as i.e. ‘the hour of nine of the day’ as opposed to ‘the hour of Vespers’ to define liturgical times.

Of course, to find evidence of a mechanical clock in Worcester at this early period would be the holy grail, but sadly none has emerged. The alternatives though seem unsatisfactory for such accurate defining of the hours. Sundials could be fairly accurate during the day, but they relied on the movement of the sun, therefore when the sun had set or it wasn’t a sunny day, they became useless. Candle clocks worked when there was no sun, so could be used on cloudy days and at night-time but their problem was poor accuracy. Time measured by candle clocks depended on the quality of the candle and the conditions in which it was burned. Some unreliable wax or a strong breeze would ruin the accuracy.

Whatever “clock” they were using allowed for accurate perception of the “hour”; they also used a twelve hour cycle as the highest hour used is the tenth hour of the day.

The earliest clocks had no face or hands and did not ring bells, they simply alerted a bell ringer who pulled the bell rope to announce it was time for Mass. Then in 1374 the monks at Worcester went further, they manufactured a ‘clock’ that rang the bell for them.

A manuscript, known as the Chronologia Aedificorum provides confirmation of this clock.

“AD 1374. In this year …….. John Lyndseye the Sacrist took the small bell of the three hanging in the clochium2 and placed it in the new campanile and caused to be made from it a horologium, vulgarly called a clock3.“

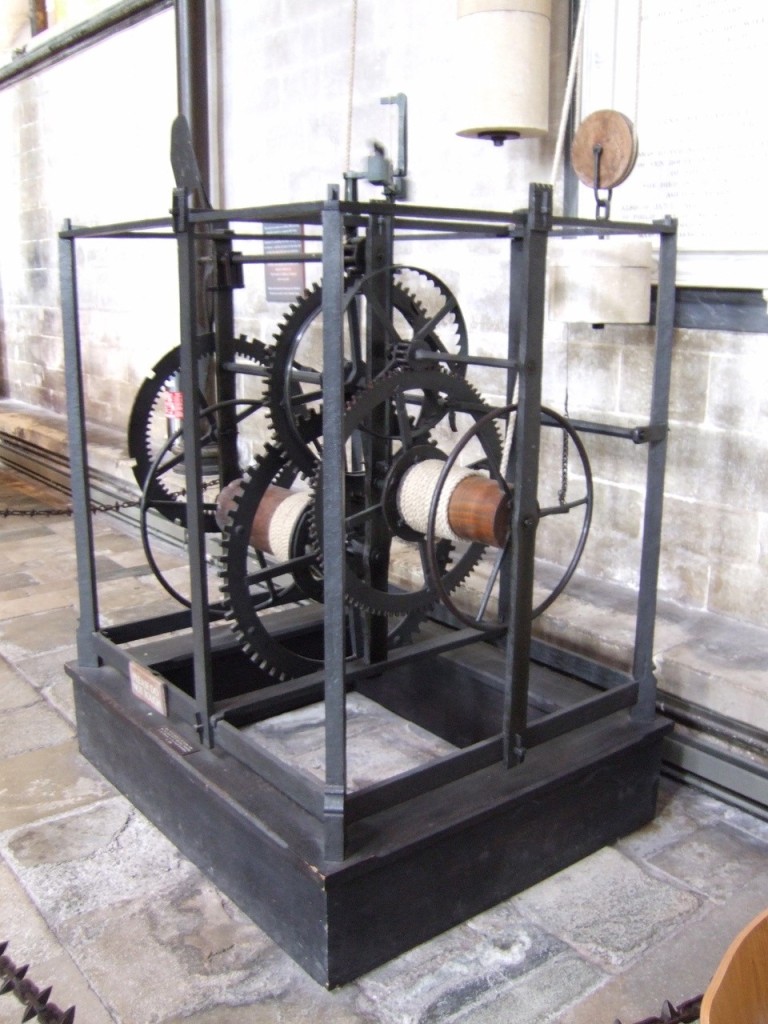

Unfortunately our clock doesn’t survive to show you, but a clock located in Salisbury Cathedral dates from c1386 and is the earliest surviving working clock in England. This clock, with its massive iron wheels and ropes extending halfway up the cathedral walls, shows more resemblance to a huge mechanical engine than the clocks we know today, but these clocks were the cutting edge of technology of their time. They could, and still can, if properly repaired and maintained, keep time to within a few seconds a week 4.

Surviving manuscript evidence suggests our clock would have been similar to the Salisbury clock, that is, it was a mechanical clock, driven by at least two weights, and thick wire was used in its mechanism. The financial accounts of the Sacrist dating from 1423/245 establish that he is paying “6s. for 2 new cords for the lead weights of the clock”. To run for 30 hours would require 22.5 meters of cord6. In the same accounts he is paying “3s for thick wire for the clock”, presumably specially made for this purpose as it was ordered from a blacksmith in Gloucester.

It fell to the Sacrist, who looked after the bells which a clock used, to manage the maintenance of the clock and for this purpose he paid a blacksmith7. It has also been suggested that blacksmiths were employed in the making of clocks 8, and looking at the iron structure of the Salisbury clock it is easy to see why.

No name is given for the blacksmith paid to maintain the clock, an Egidio Smythe maintained the bells during the early C15th and it may have been him, but as every blacksmith I found in the manuscripts has the name ‘Smythe’ and they may have used a specialist for the clock it is hard to be certain.

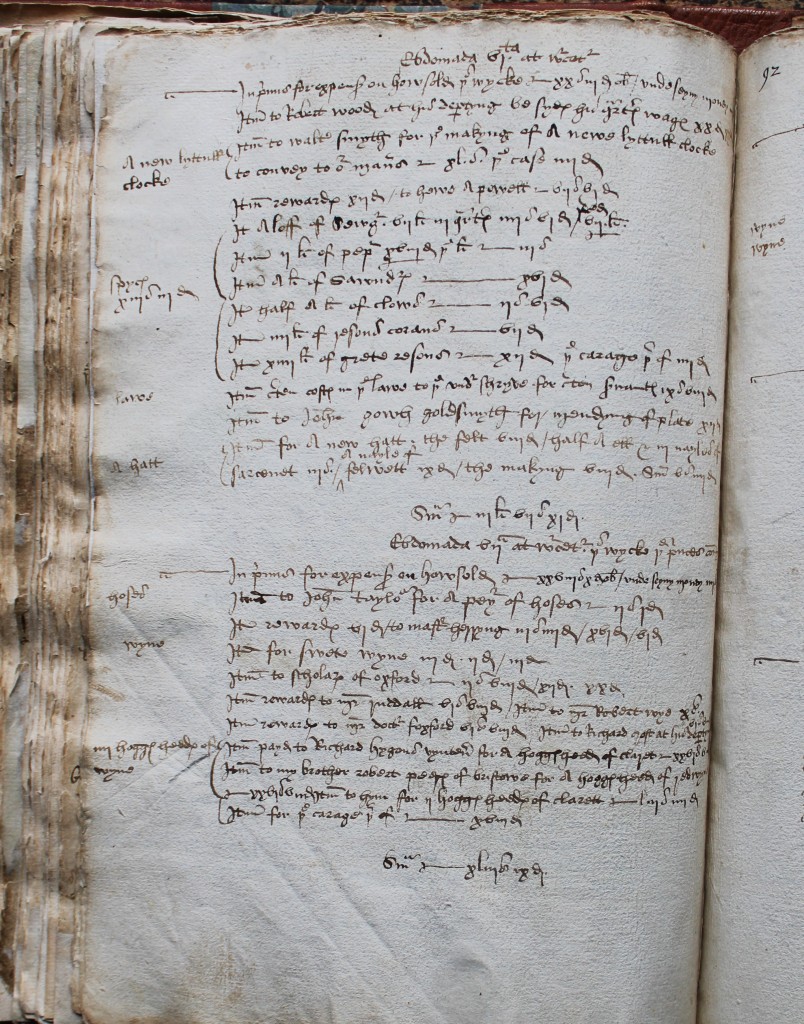

Nevertheless, by the early C16th specialist clockmakers appear in the accounts and they were certainly multi-skilled; in 1527 Prior More paid Walter Marshe, ‘ye clock maker’ for performing surgery on his arm!

Prior William More, one of the last priors before the dissolution, was the most worldly and flamboyant of our priors. He actually spent little time in the monastery, preferring to enjoy the life of a country squire on his three favourite estates, Crowle, Battenhall and Grimley. All three manors are several miles outside Worcester so he needed his own clock to tell the time for Mass and he had his own ‘litel clock.’ This personal clock must have been relatively ‘portable,’ as in 1521 he is sending it to London to be repaired9 – so not the type of clock used at the Cathedral.

Maybe he got tired of moving his clock around with him as in 1525 he also has ‘a new ‘lyttull clocke’ made to ‘convey to our maners’10 [manors] at a cost of 41s and a case for it an extra 4d. As some sixteen manors were allocated to the Prior it is unlikely that he had a clock for each one, possibly it was for one or more of his favourite manors.

The maker of this clock is named as Walter Smyth, the surname ‘Smyth’ may suggest he [or his forebears] was also a blacksmith. Prior More also paid a Gloucester blacksmith for ‘dressyng’ of his clock. The term ‘dressyng’ is puzzling as it also used in the context of ‘dressyng vi cappis’ [caps], ‘dressyng of my hatt with selke’ and of books, ponds, boots, horses, torches and even drawers!11

When first made, the earliest cathedral clock was placed in the ‘new campanile’ or bell tower, but at some point, may have been moved to the Clochium. This Clochium or the Leaden Steeple, was a separate octagonal tower to the north of the Cathedral, some 65 meters in height, high enough to accommodate the clock mechanism and the cords and weights needed to power it. In 1647, when it was demolished, the bells it contained were sold for scrap and one of these, described as ‘the clock bell’, was inscribed ‘Thoma Mildenam priore’, Thomas Midenham was Prior from 1455 to 1507. It is tempting to think there was more than one clock, but more likely the original 1374 bell used by John Lyndesey for the clock had cracked and been replaced. One of the other bells was inscribed ‘Johannes Lyndesey, hoc opere impleto, Christi virtute faveto,’ probably one of the two bells he had made in 138212 .

The Salisbury clock, despite its extraordinary appearance, still does the job it was made for, tolling a bell every hour, as it has done for some 600 years, but unfortunately our Worcester clock is long gone. When did it go? That I have yet to discover, so watch this space!

Vanda Bartoszuk

Bibliography:

Ethel Fegan (ed.), The Journal of Prior William More, Worcestershire Historical Society 1914 [Parts One and Two, WCL/6.2.16a, 6.2.16b]

Noake J, The Monastery and Cathedral of Worcester, Longman, 1866 [WCL/4.7.34]

Richard of Wallingford, abbot of St Albans 1326-1335′, Trans. St Albans and Herts AAS, 1926, 221-39

Salisbury, Wells and Rye – The Great Clocks Revisited, Antiquarian Horology, Volume 39, No. 3 (September 2018), pp. 327–341

Scobie-Youngs, K, English Church Clocks.

Watson, S 2010, ‘The Culture of Medieval English Monasticism’, English Historical Review, vol. 125, no. 512

- WCM A1 ↩︎

- This clochium was a huge medieval bell tower that stood separate from the cathedral on the north side, demolished c.1647. ↩︎

- WCM AXII folio 77b ↩︎

- Keith Scobie Youngs, Cumbria Clock Company [Pers. Comm] ↩︎

- WCM C425 ↩︎

- Keith Scobie Youngs, Cumbria Clock Company [Pers. Comm] ↩︎

- WCM A12 folio 35 [1515] ‘Farrario per custodi cymbali & orologii- a blacksmith to maintain the cymbals and the clock. ↩︎

- Scobie-Youngs, K, Salisbury, Wells, and Rye- The Great Clocks Revisited, Antiaquarian Horology volume 39 (no. 3, September 2018), pp.327-341. ↩︎

- WCM A11 folio 62 ↩︎

- WCM A11 folio 91 ↩︎

- Ethel Fegan (ed.) The Journal of Prior William More, Worcestershire Historical Society 1914 parts 1 and 2 [WCL 6.2.16a +6.2.16b] ↩︎

- WCM A12 ↩︎

Absolutely fascinating, thank you so much for sharing your research.

LikeLiked by 1 person