Seville would have been an interesting place at the turn of the 16th Century. Columbus had encountered the Americas only within the last decade, but already strange goods and stranger stories (probably involving promises of untold wealth) were pouring into the great Spanish port city. Some of the stories of untold wealth found currency amongst certain circles. When an expedition set out from Spain in February 1502, under the command of Nicolas de Ovando, he took some 2500 colonists with him.

These colonists were no desperados, but willing volunteers, carefully selected to represent a cross section of contemporary Spanish society. The Spanish pattern of overseas settlement differed from that of the Portuguese, Dutch or British. Instead of establishing fortified trading stations (known as ‘factories’ in the Early Modern Period), they sought to settle areas permanently, develop them economically, and compel indigenous peoples to work for them in return for vague promises of protection. Known as encomienda, this system sought to translate the administrative structures of Spain onto the New World, with the addition of slave labour.

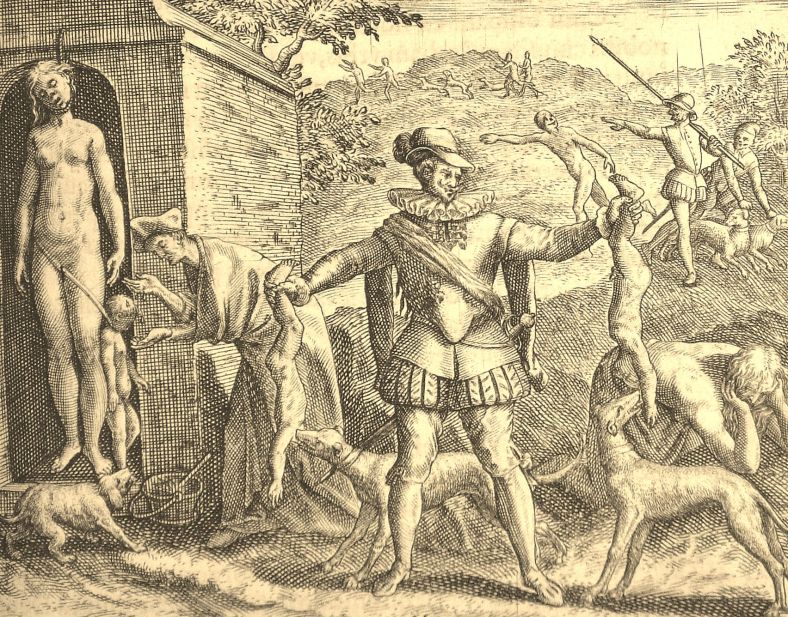

Illustration by de Bry to 1598 edition of Las Casas. Image Copyright the Dean and Chapter of Worcester Cathedral (UK)

Civil servants, priests and merchants would be required just as much as soldiers and sailors – and so we find Pedro de las Casas, a trader of Seville, sailing on de Ovando’s expedition, together with his teenage son Bartolomé. In time, the two men established their own country estate, or hacienda, worked by slaves. As Bartolomé grew older, he would take part in slave-raiding activities, and joined in with the conquest of Cuba in 1513.

Campaigning in the New World at this time would not have been pleasant. Indigenous Americans, separated from the rest of humanity for thousands of years, were easy prey for Eurasian diseases such as small pox. Those lucky enough not to die in agony and covered in reputuring pustules then faced the danger of Spanish steel and firearms. The generally huge cultural gulf between the Arawak natives in the Caribbean and the European settlers led to them having some pretty mutually unsympathetic views of each other. All too often, the Spanish would see the indigenous peoples as backward, savage and not fully human.

Disease, blood, xenophobia, sadism, misery and the stench of blood would have been rife – and would certainly have had a great effect on a young man. Although Bartolomé initially joined in with the exploitation of Hispaniola and Cuba, he seems to have gradually grown more and more disgusted with the behaviour of his fellow men. He was ordained as a priest in 1510 – evidence of his profound religious convictions, but not of his humanity at the time – for the next year he publically spoke up against a visiting Dominican Friar who decried the injustice of the encomienda system. But in 1514, he seems to have had an epiphany, and gave up his slaves and his hacienda. Encouraging other settlers to follow his example was not a move which made him very popular, and so he returned to Spain in 1515.

Illustration by de Bry to 1598 edition of Las Casas. Image Copyright the Dean and Chapter of Worcester Cathedral (UK)

Bartolomé de Las Casas would spend the next 50 years of his life campaigning for an end to slavery and the exploitation of indigenous peoples. As a human rights campaigner, he was not only amongst the first, but also one of the most dedicated. His career in this regard had many ups and downs, but he did succeed in encouraging Spanish King Charles I (styled Charles V as Holy Roman Emperor) to pass Leyes Nuevas, or ‘The New Laws’ in 1542, granting native Americans at least some form of legal protection .

He continued his work, publishing Brevísima relación de la destrucción de las Indias (‘A short account of the destruction of the Indies’) in 1552, before he died four years later. We have a copy of this book in Worcester Cathedral Library – a later edition of 1598. This edition – illustrated and published by Theodore de Bry in Frankfurt – has its own curious tale to tell about politics and religion is 16th Century Europe.

Spain was Europe’s leading power in the 16th Century. Like leading powers have been forever, its position was resented by its neighbours. Resentment boiled over to hatred in areas where Spain had been throwing its weight around – particularly in the Low Countries (where a revolt against Spanish rule began in 1566) and England (target of a Spanish invasion, the Armada of 1588). This hatred was also fuelled by sectarian divide – the Anglo-Dutch protestants on one side against the catholic Spanish.

Illustration by de Bry to 1598 edition of Las Casas. Image Copyright the Dean and Chapter of Worcester Cathedral (UK)

Theodore de Bry, the publisher of our book, was a citizen of Liege (in modern day Belgium) who, as a protestant, had been treated roughly by the Spanish authorities, and forced to flee with his family, eventually settling in Frankfurt (via Strasbourg, Antwerp and London). A gifted engraver, his main business was to provide illustrations of exotic locations for travel books. He would have had to rely much on his imagination, as he never left Europe. Yet the text written by Bartolomé de las Casas on New World atrocities provided him with more than enough information to make these graphic, arresting pictures.

Was de Bry motivated to publish his updated version of Las Casas’s work by his shared concern for the plight of indigenous peoples in the Americas, or was he merely on to a money-spinner? Or perhaps he had an altogether different ambition.

Illustration by de Bry to 1598 edition of Las Casas. Image Copyright the Dean and Chapter of Worcester Cathedral (UK)

The unpopularity of the Spanish in North Western Europe had led to a huge surge in the publication of tracts and diatribes against them – portraying Spaniards as cruel, bigoted and un-Christian. So great was this demonization of the Spanish nation and its people through propaganda that later (Spanish) historians labelled it as La Leyenda Negra, or ‘The Black Legend.’ Could de Bry have been part of this movement? Subconsciously, he certainly was – ‘The Black Legend’ did tend to focus on Spanish colonial atrocities, and de Bry was one of the best sources for this. Whether or not he was motivated by the treatment he himself had received at Spanish hands, however, remains a matter for debate.

Another question too is just why we do happen to have a copy at Worcester Cathedral Library. As an Anglican organisation, we have historical books and pamphlets that both champion Christian clemency and (in accordance with the social mores of Early Modern England) denounce Catholicism and its chief agent, the King of Spain. Was our book bought by a clergyman with a deep sense of humanitarian concern, or by one who was sceptical of contemporary Spanish foreign policy?

Tom Hopkins