Certainly since the sixteenth century, and most probably earlier, Worcester Cathedral performed an annual audit of its finances. We think of audits as being official examinations of accounts, or periodical settlements of accounts between landlords and tenants. In our modern commercial times the pressures and strains of the annual audit are such that the collective release felt in businesses after their completion is tangible, if not a cause for minor celebration. Researching back through the Cathedral Library archives it seems we are not alone in this sense of release, although our forebears brought a whole new meaning to the post-audit celebration.

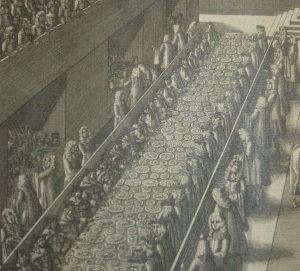

An example of a 17th Century Feast – the Knights of the Garter feasting at Windsor during the reign of Charles II

Image copyright the Dean and Chapter of Worcester Cathedral (UK)

In the Cathedral Library archives we have a fascinating collection of manuscripts detailing various regulations, fees, accounts, receipts, bills, and lists of supplies, the earliest dating back to 1642. From these contemporary records we start to see that the annual audit at Worcester involved a considerable expenditure, so much so that it was felt necessary to place certain restrictions upon this expenditure. Hence, according to John Noake, in 1593 assertive action was taken in the form of a Chapter order, which attempted to implement a cap of “forty marks” over and above normal expenses, and in addition enforced a penalty of “five marks” should any treasurer subsequently make a request or demand of the Church for any further allowance, and the same amount should be deducted from his stipend by the next treasurer.

But what was the reason for this action? And what can the surviving manuscripts tell us?

Well certainly they tell us that the audit “feasts” as they were termed, were extravagant affairs, and became especially so after the restoration of Charles II. At this time Henry Roper and Harry Green were the cooks and caterers at the Cathedral, and Barnabas Oley was the treasurer. The manuscripts in the Library archives include many lists and menus drawn up by, or on behalf of, these men, and shed light on both the breadth and quality of provisions laid on. For example, the sums recorded for October 1661 include three bills for £5 2s 2d, £12 6d and 12s 4d. In addition a bill of £30 15s 8d for wages, pewter hire, linen hire, making clean rooms at the Deanery, and sundry provisions. But there is more! A further £3 was for pay (including that for butlers) and included “the sum of Thirty Shillings was payd Mr. Roper for Catering at the Audit”; and yet a further sum of £27 15s 8d “for the Charges of the Auditt in Totall.” Altogether a prodigious sum.

The top of page 2 of an audited itemised food bill (D171)

Image copyright the Dean and Chapter of Worcester Cathedral (UK)

In addition to these provisions a “black-guard” was hired to take care of the various pots, dishes and cooking utensils. A man was sent round the city to invite gentlemen to “assist” at the feast, whilst another man on a horse was dispatched to invite leading gentlemen of the county. Certain provisions for the feasts were acquired by other means too; some gentlemen were obliged to send gifts in return for free rights to hawking, hunting, and fishing and fowling; these gifts included pheasants and partridges. Tenants’ gifts were also numerous, including such extravagancies as boar’s head and spiced wine, or supplies of venison.

There are also references to bonfires being lit on College Green, and fireworks let off there in celebration of the frustration of “the plot”. (The Gunpowder Plot)

Another example of a 17th Century Feast – the Coronation Feast of James II in Westminster Hall

Image copyright the Dean and Chapter of Worcester Cathedral (UK)

By the late seventeenth century the resulting expenditure had again become so great that yet another attempt was made to cap it to a maximum figure of fifty pounds, until such time that the Church was out of debt (let’s not forget that there was at this time a large outlay on restoration of the fabric of the Cathedral and its properties following the civil war).

By the late eighteenth century we have evidence of tighter regulations for the audit being implemented. These regulations, written in a neat contemporary hand, include:

“That on the first day of the Audit, the several Members of the Cathedral be invited, as usual, to Dine in the Audit Hall …”

“That no Provision of any Sort be carried by any Servant out of the Audit Hall”

“The allowance to the Prisoners in the Goal to be continued.”

“That no Maderia Wine be used, but Lisbon or Sherry, if White Wine be called for.”

[No mention of sherry is made in the seventeenth century Cathedral accounts, although Noake tells us that it is mentioned in the Worcester Corporation accounts in 1666 “owing perhaps to the then recent treaty with Portugal.”]

An audit showing 2s 9d spent on ale for prisoners at the castle in Worcester, given by the Dean and Chapter (D187)

Image copyright the Dean and Chapter of Worcester Cathedral (UK)

In other accounts lists we see sums set aside for the chimneys to be swept, and for the porter for summoning the corporation and clergy to the feast. And in 1724, itemed amongst the audit expenses was “a cocoa-nut cup” mounted with silver, and priced at £3 7s. In addition knives, forks and pewter were hired, and frequent charges made for plates that had been accidentally melted!

A brief survey of audit feasts throughout the late seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries reveals that annual expenditure was often great, for example in 1669 it was £70 9d, in 1724 it was £42 18s 8d, and in 1763 it was £76 7s 2½d.

By 1765 the overall expenditure had risen to an alarming £82 19s 11d [see note on relative values below]. The associated receipts in the Cathedral archive list provisions bought in, include:

“pig meat, sausages and forcemeat, greengroceries (vegetables and herbs), sweet puddings and savouries, 5 tons of coals, ale for prisoners [11 quarts at a cost of 2s 9p], for cutlery lost [namely one large table spoon and 2 tea spoons at a total cost of 18s 10p], spices, sugar, dried fruit, tobacco, meat and fish, for hire of cutlery and utensils, cleaning materials, candles, broken glass and earthenware, malt and hops”

Another detail of the Coronation Feast of James II in Westminster Hall

Image copyright the Dean and Chapter of Worcester Cathedral (UK)

At some point, according to Noake, we start to see the annual audit feast conflated with other local traditions. He tells us that on 25th November (St. Catherine’s day) it was a custom of the Dean and Chapter (this being the last day of the annual audit) to distribute amongst the inhabitants of the precincts a “rich compound of wine, spices etc.” which was specially prepared for the occasion. We have a record from the Dean in 1848 that this custom was kept up to that time. Noake speculates that this may have been a legacy of the ancient Worcestershire custom of “catherning”, and describes it as a time when “young people made merry on her day … roasting apples on a string till they dropped into a large bowl of spiced ale, which was then called lamb’s wool”.

Human nature as it is, we have always been eager to celebrate events, however minor or mundane they may seem. But in the history of the Worcester Cathedral audit feasts we witness a most curious coming together of the prosaic and the extravagant.

Steve Hobbs

Note on relative values: To give you an idea of the level of the costs to be able to see just how much was spent on the feasts we know that the Cathedral’s entire annual expenses came to £1773 2s 8d in 1765 and that the Audit bill of £82 quoted above actually rose to £113 26s 9d by the time the final accounts were signed off. So roughly 5 or 6% of the Cathedral’s annual expenditure that year went on just one feast. To get an idea of how that would compare to an average annual salary, a skilled and respected position in the Cathedral structure, such as the Cathedral School’s senior teacher earned £20 per year and his deputy earned £10. Similarly, the Choirmaster earned £8 per year. Ordinary jobs, such as the Cathedral’s cooks, butlers and gate keepers, earned a salary of £5 per year or 4% of the amount of money they spent on the feast.

Bibliography

The Monastery and Cathedral of Worcester by John Noake. London, Longman & Co., 1866. [4.7.35]

Manuscripts [D165-D191] Worcester Cathedral Library – comprising various regulations, fees, accounts, receipts, bills, and lists of supplies.

Worcester Cathedral A62 Cathedral Treasurer’s Register

One thought on “Feasting and Finance: The Curious History of Audit Feasts at Worcester Cathedral”